When corporations ransack countries: a primer on investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS)

“If you wanted to convince the public that international trade agreements are a way to let multinational companies get rich at the expense of ordinary people, this is what you would do: give foreign firms a special right to apply to a secretive tribunal of highly paid corporate lawyers for compensation whenever a government passes a law to, say, discourage smoking, protect the environment or prevent a nuclear catastrophe. Yet that is precisely what thousands of trade and investment treaties over the past half century have done, through a process known as ‘investor-state dispute settlement,’ or ISDS.”

This is how The Economist introduced its readers to a once unknown element in international trade and investment agreements. The business magazine referred to ISDS as “a special privilege that many multinationals have abused”[1]. Since the publication of the article, hundreds of additional ISDS cases have been started by investors against states across the world. Recently the Australian mining magnate Clive Palmer has used a mailbox company in Singapore to sue his own country for a whopping US$ 280 billion. Australia’s supposed crimes? A court had denied the permits for a coal mine and power plant on climate change grounds and, in a separate case, Palmer didn’t get the necessary permits for an iron ore mine.[2]

The ISDS system, with its roots in colonialism and extractivism, is not fit for purpose in the twenty-first century because it prioritizes the interests of foreign investors over the rights of States, human rights and the environment.

David R. Boyd, UN Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment[3]

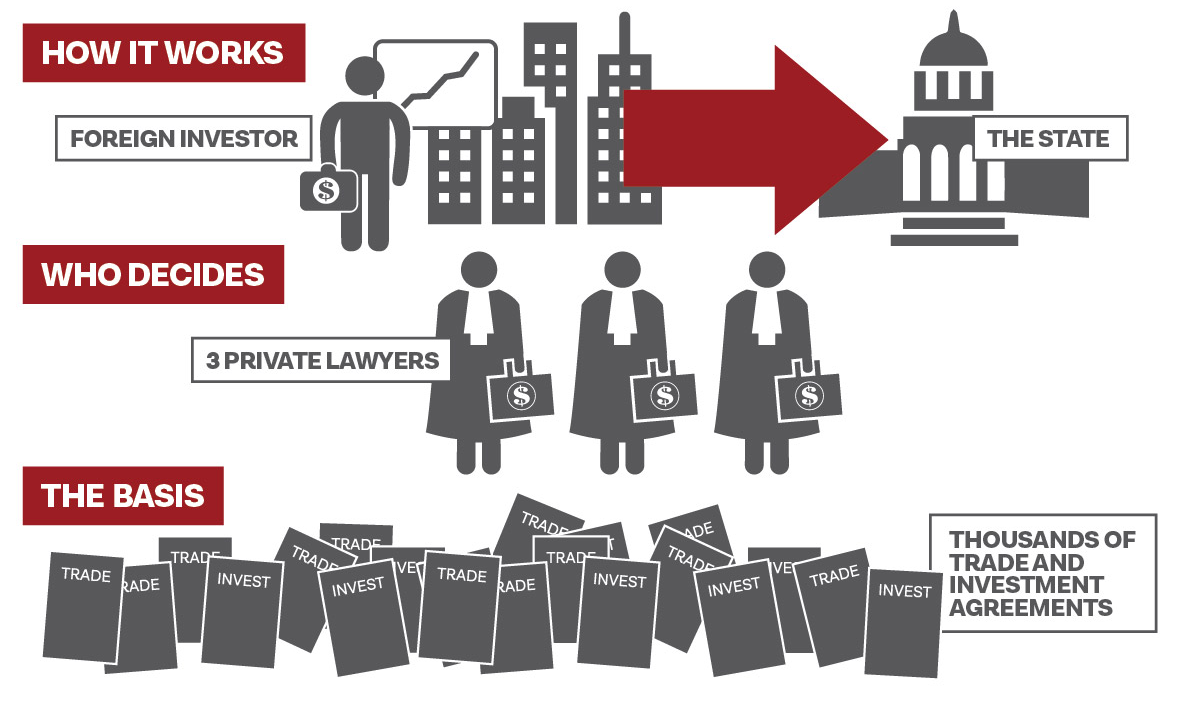

The legal basis for these investor-state dispute settlements – known under the acronym ISDS – are over 2,635 international trade and investment agreements in force between states worldwide.[4] These agreements give sweeping powers to foreign investors, including the peculiar privilege to directly file lawsuits against states at international arbitration tribunals. Corporations can claim compensation for actions by host governments that have allegedly damaged their investment, either directly through expropriation, for example, or indirectly through virtually any kind of regulation. ‘Investment’ is interpreted so broadly that mere shareholders and rich individuals can sue, and corporations can claim not just for the money invested, but for future anticipated earnings as well.

RED CARPET COURTS

ISDS claims are usually decided by a tribunal of three private lawyers – the arbitrators – who are chosen by the litigating investor and the state. Unlike judges, these for-profit private sector arbitrators do not have a flat salary paid for by the state, but are in fact paid per case. At the most frequently used tribunal, the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), arbitrators make US$500 per hour worked.[5] In a one-sided system where only the investors can bring claims, this clearly creates a strong incentive to side with companies rather than states – because investor-friendly rulings pave the way for more lawsuits and more income in the future.

THE CHRONOLOGY OF AN INVESTMENT ARBITRATION

The process starts when a foreign investor sends a notice of arbitration to a state. Unlike in other areas of international law, the claimant does not have to go through local courts first. Both the investor and the state will be assisted by lawyers (counsel) during the proceedings.

The investor and the state jointly select the arbitration tribunal. Usually each party picks one arbitrator and both jointly appoint a third to serve as president. The arbitrators are private, for-profit lawyers, not judges, who are paid by the case.

Proceedings last years and mostly take place behind closed doors, with scant or no information at all released to the public, sometimes not even the fact that a case is happening.

The arbitrators ultimately determine, based on the investment treaty that was used to file the case, if the state violated the investor’s rights and the size of the remedy. They also allocate the legal costs of the proceedings, which average more than US$10 million.[6] Opportunities to challenge the rulings are extremely limited.

States have to comply with arbitral awards. If they resist, the award can be enforced by actual courts almost anywhere in the world by seizing the state’s property elsewhere (for example, by freezing bank accounts or confiscating state aircraft or ships).

Weapons of legal destruction

Since the late 1990s, the number of lawsuits taken by investors against states has surged – and so has the amount of money involved (see box 1 below). The last two decades have also seen multibillion-dollar claims alleging damage to corporate profits as a result of legislation and government measures in the public interest. Developed and developing countries on every continent have been challenged by corporations for trying to introduce regulations to promote: financial stability measures, bans on toxic chemicals, mining restrictions, anti-discrimination policies, environmental protection laws, policies to phase out fossil fuels and more. A lawyer who has defended many governments in these lawsuits has hence called investment treaties “weapons of legal destruction”.[7]

It’s litigation terrorism.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz on ISDS[8]

Sometimes, just the threat of an expensive dispute has been enough to freeze or delay government action, with policymakers realising that the cost of public interest regulation is too much for the state to bear. Five years after the foreign investor rights in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, a former Canadian government official told a journalist: “I’ve seen the letters from the New York and DC law firms coming up to the Canadian government on virtually every new environmental regulation and proposition in the last five years. They involved dry-cleaning chemicals, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, patent law. Virtually all of the new initiatives were targeted and most of them never saw the light of day”[9].

Box 1: Striking figures from the world of ISDS[10]

- Investor-state legal cases have mushroomed in the last two decades, from a total of six known treaty cases globally in 1995 to a record high of over 60 new claims filed annually since 2013.

- 72% of all ISDS cases globally were based on bilateral investment treaties, concluded between two countries. 65% of all ISDS cases that have been filed were based on investment agreements concluded in the 1990s.

- Globally, 1401 disputes against 136 countries have been recorded throughout the history of ISDS as of 1 January 2025, but due to the lack of complete and transparent publicly available information the actual figure could be much higher.

- In the known cases for which this information is available, investors have sued governments for the total sum of more than US$1.1 trillion. This is far more than all Foreign Direct Investment flows to countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America in 2024.

- Investors have triumphed in 59 per cent of investor-state cases where there has been a decision on the merits of the case, whereas states have ‘won’ only 41 per cent of the time (even though states can’t ever win through ISDS, only not lose and thus succeed in avoiding having to pay out damages).

- About 17% of ISDS cases end in settlement, most likely involving payments by governments or changes in laws and regulations to appease disgruntled investors, often in partial or total secrecy, meaning citizens don’t know where their public money went, or why a policy was changed.

- The total amount of money which states have thus far been ordered or agreed to pay in disclosed ISDS rulings and settlements is more than US$110 billion – a startlingly large figure, which is equivalent to all Foreign Direct Investment to countries in South America in 2024.

- Because ISDS proceedings are often kept partially or fully secret, the amounts involved are almost certainly higher. Academic research from 2022 estimates that claims totaling US$ 186 billion and payments of US$ 15 billion to investors have not been reported due to secrecy.[11]

- The average amounts investors claim and win have increased over time. Whereas the average claim was almost US$ 750 million between 1987-2014, this increased to almost US$ 1 billion for 2015-2024. For the same time periods, the amounts won by investors more than doubled from almost US$ 100 million on average to more than US$ 230 million.

- The economic sectors where most ISDS cases are filed are mining, oil, gas and coal extraction and energy supply. Combined, they make up 34% of all disputes and for cases filed in 2024 their share even reached 59%.

- More than half of all ISDS cases globally (56%) involve investors from a European country, making European companies the by far most aggressive users of the system. The problem is compounded by the fact that mailbox companies in countries like Luxembourg, Cyprus and the Netherlands have been used to sue countries around the world.

Investment arbitration in dire straits: a global storm of opposition

The growing number of corporate lawsuits has raised a global storm of opposition to ISDS, from across the political spectrum. Around the world public interest groups, trade unions, community groups and academics have repeatedly proclaimed opposition to ISDS and urged governments to exit from the regime.[12] Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative in Trump’s first term, highlighted the damage to the ability to regulate in the public interest in a testimony to the US Congress: “we’ve had situations where real regulation which should be in place which is bipartisan, in everybody’s interest, has not been put in place because of fear of ISDS.”[13] Judges have also raised concerns, stating that “the creation of special courts for certain groups of litigants is the wrong way forward.”[14]

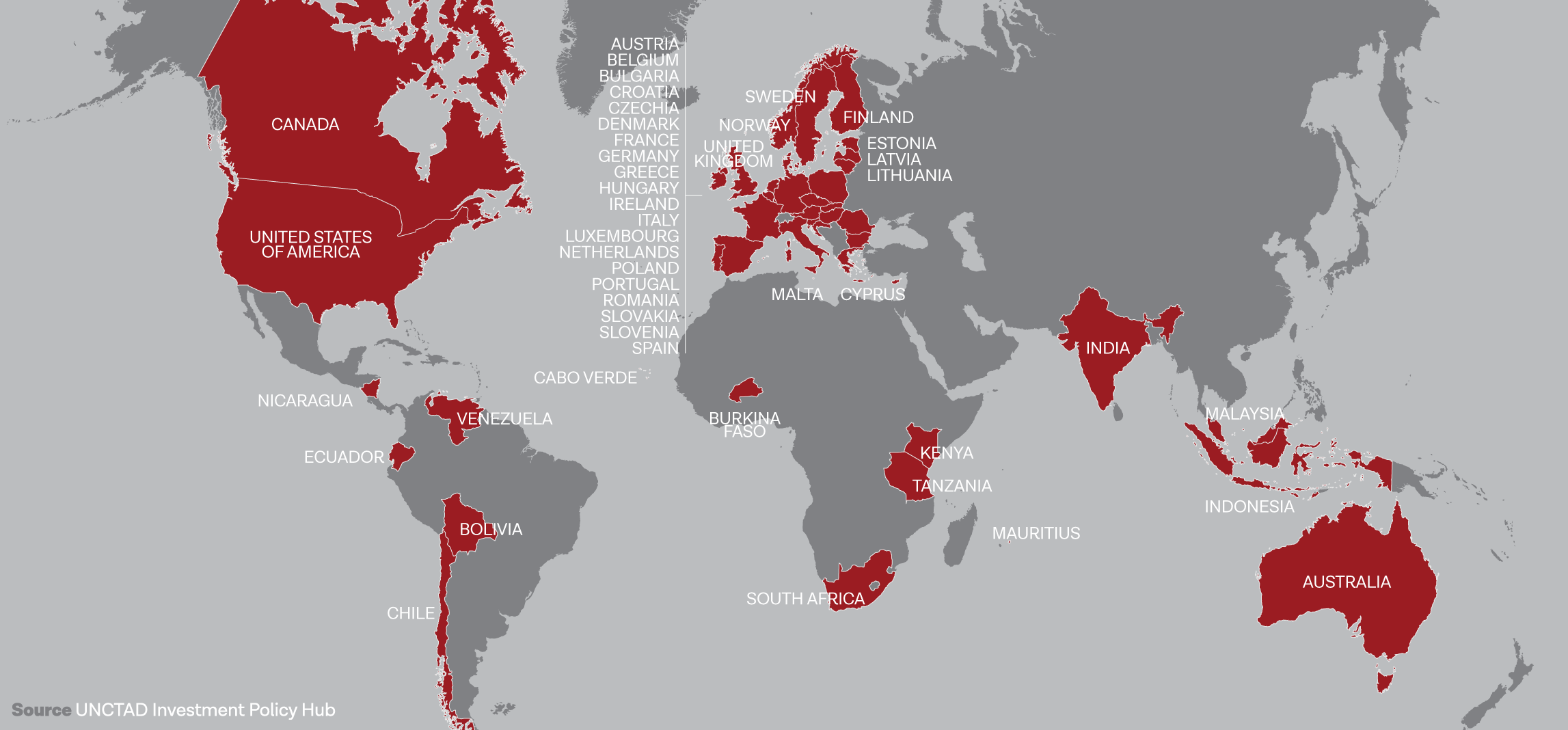

Some countries, too, have realised that the promised benefits of investment arbitration have not materialised (see box 2 below) and are trying to escape from the system. South Africa, Indonesia, India, Ecuador, Bolivia and other countries have terminated all or some some of their bilateral investment treaties (BITs). EU member states have started to terminate all their bilateral treaties with each other – roughly 200 agreements.[15] Globally more than 400 BITs have been terminated without being replaced.[16] The United States and Canada terminated ISDS between themselves as they renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement.[17] 11 European countries and the EU itself left the Energy Charter Treaty, a large ISDS deal for the energy sector.[18]

The EU has taken the final step to exit the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) … which is not compatible with the EU’s climate and energy goals under the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement.

European Commission Press Release[19]

Box 2: Busting the myth that investment agreements and ISDS bring investment

ISDS supporters argue that “international arbitration is an important protection … designed to attract foreign direct investment.”[20] They claim that the right to sue states in “neutral” dispute resolution fora outside of domestic courts has a particularly positive effect – because it serves as a “check” to the alleged “arbitrary or unlimited use of government power”, increasing “the desirability of a State as a potential inward investment destination”.[21]

This may sound plausible to some, but there is one major problem with this argument: there is no clear evidence that investment agreements actually bring investment. A meta-analysis of 74 academic studies on the topic found investment agreements “to have an effect on FDI that is so small as to be considered as negligible or zero.”[22] Qualitative research suggests that for the vast majority of investors, investment treaties are not a decisive factor when they go abroad.[23]

Governments have also begun to realise that the promise of foreign direct investment (FDI) has not been fulfilled. After South Africa cancelled some of its investment treaties, an official explained: “South Africa does not receive significant inflows of FDI from many partners with whom we have BITs, and at the same time, continues to receive investment from jurisdictions with which we have no BITs. In short, BITs have not been decisive in attracting investment to South Africa.”[24] This has also been the experience elsewhere; Brazil, for example, receives the largest amount of FDI in Latin America[25] – despite never having ratified a treaty allowing for ISDS. In Indonesia, FDI from the Netherlands increased by 19.2 per cent in 2015 – even though the country had terminated its investment treaties with the Netherlands and several other countries the year before.[26]

More importantly it is now widely acknowledged that while FDI may contribute to development, its negative impacts can be substantial, while the benefits of FDI are far from automatic. Regulation is needed to generate positive effects locally, such as decent jobs, generation of tax revenues, or technology transfer – and to avoid the risks that FDI can pose to the environment, local communities etc. Investment agreements are not only agnostic on these crucial development issues, protecting investments irrespective of their nature and impact, but their “pro-investor imbalance can (also) constrain the ability of governments to regulate in the public interest”, as an official of the Government of South Africa put it.[27]

More urgent than ever to leave the toxic treaties

While some governments have started to free themselves from the ISDS regime, others are continuing to work on its expansion. ISDS was included in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, signed by 11 states from the Pacific, Chile, Mexico, and Canada) and several bilateral deals, including agreements between the EU and Canada, Singapore, Vietnam, Chile and Mexico. The EU also plans to scale up – and re-legitimise – ISDS via a permanent global court for investor-state disputes.[28]

But activists and campaigners fought successfully to keep ISDS out of the largest trade deal ever signed, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), involving 15 countries in East and South East Asia. And they have pushed governments to exit treaties, like the Energy Charter Treaty, that are among the most dangerous for climate action.

However, many of the old investment treaties that were concluded in the 1990s and 2000s continue to be used by investors, especially from Europe, to sue governments and extract compensation for them. At a time when government budgets are under pressure by high interest rates and increasing expenditures, it is imperative for countries to free themselves from the shackles of ISDS and minimize the threat that ISDS poses to public finances and their ability to regulate in the public interest.

To finally free themselves and our democracies from ISDS, governments should therefore:

- Stop signing on to new treaties that contain ISDS.

- Start terminating old treaties that continue to cause harm.

- Work with likeminded countries to towards a global termination treaty that ends many investment treaties at once.

A total of 412 investment treaties had been terminated by end of 2024

[1] The Economist: Investor-state dispute settlement – The arbitration game, 11 October 2014.

[2] For an overview of the Palmer cases, see: Patricia Ranald: Clive Palmer’s foreign investor claims against Australia now $420b, Pearls and Irritations, 10 January 2025.

[3] David R. Boyd: Paying polluters: the catastrophic consequences of investor-State dispute settlement for climate and environment action and human rights, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, 13. July 2023.

[4] UNCTAD’s International Investment Agreements Navigator gives the best overview of existing international investment agreements

[5] ICSID: Memorandum on the Fees and Expenses (2022).

[6] Matthew Hodgsen et al: 2021 Empirical Study: Costs, Damages and Duration in Investor-State Arbitration, British Institute of International and Comparative Law, Allen & Overy, June 2021.

[7] George Kahale, III: Keynote Address at the 8th Investment Treaty Arbitration Conference, Prague, 25 October 2018, 1.

[8] Sebastien Malo: U.N. reform needed to stop companies fighting climate rules – Nobel laureate Stiglitz, Reuters, 29 May 2015.

[9] Quoted in: William Greider: The Right and US Trade Law – Invalidating the 20th Century, The Nation, 17 November 2001.

[10] Unless noted otherwise, the statistics listed here are from: UNCTAD: Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator; UNCTAD: World Investment Report 2025: International Investment in the Digital Economy.

[11] Sebastian Puerta & Tim R Samples: Investment Law’s Transparency Gap, Cornell International Law Journal, 2022.

[12] For example: Global Civil Society Sign-on Letter on UNCITRAL’s Investor-State Dispute Settlement Reform Discussions, 30 October 2018; 300+ Professors of Law, Economics Urge Biden to Eliminate ISDS in US Trade Agreements, 15 April 2024.

[13] The Statement was reproduced by: Simon Lester: Brady-Lighthizer ISDS Exchange, International Economic Law and Policy Blog, 21 March 2018.

[14] Deutscher Richterbund: Stellungnahme zur Errichtung eines Investitionsgerichts für TTIP – Vorschlag der Europäischen Kommission vom 16.09.2015 und 12.11.2015, Nr. 04/16, 4 February 2016.

[15] European Commission: Declaration of the Member States of 15 January 2019 on the legal consequences of the Achmea judgment and on investment protection, 17 January 2019.

[16] UNCTAD: World Investment Report 2025: International Investment in the Digital Economy.

[17] Nathalie Bernasconi-Osterwalder: USMCA Curbs How Much Investors Can Sue Countries—Sort of, IISD Insight, 2 October 2018.

[18] See: End Fossil Protection: Latest News.

[19] European Commission: EU notifies exit from Energy Charter Treaty and puts an end to intra-EU arbitration proceedings, Press Release, 28 June 2024.

[20] Tom Sprange QC et al: Chapter 35 – Enforcement of Awards, in: The Investment Treaty Arbitration Review 6th Edition, June 2021.

[21] Energy Charter Secretariat: Programme of action to address energy poverty: focus on Africa, 2009, 14.

[22] Josef C. Brada et al.: Does Investor Protection Increase Foreign

Direct Investment? A Meta-Analysis, Journal of Economic Surveys, 2020.

[23] Jonathan Bonnitcha: Assessing the Impacts of Investment Treaties: Overview of the evidence, September 2017, 3-4, 10.

[24] Xavier Carim: International Investment Agreements and Africa’s Structural Transformation: A Perspective from South Africa, South Centre Investment Policy Brief No. 4, August 2015, 4.

[25] UNCTAD: World Investment Report 2025: International Investment in the Digital Economy.

[26] Transnational Institute: Why did Ecuador terminate all its bilateral investment treaties?, 2017.

[27] Xavier Carim: International Investment Agreements and Africa’s Structural Transformation: A Perspective from South Africa, South Centre Investment Policy Brief No. 4, August 2015

[28] For a critical assessment of the proposed Multilateral Investment Court, see: Friends of the Earth Europe: The Multilateral Investment Court Locking in ISDS, November 2017.

[29] Data from: UNCTAD: International Investment Agreements Navigator.